Netherlands v. Germany

Painting / Malerei

21/10/2006 t/m 22/01/2006

The title of this exhibition refers to the rivalry that is part of the collective subconscious of the Netherlands and Germany. The difference in size between the two neighbouring nations has produced a strong David-and-Goliath complex. This is, however, much more deep-rooted in David than in Goliath, as witness the grossly disproportionate euphoria that swept the nation in 1988, when the Dutch team carried off the European Cup with a 2-1 score, achieved in the final moments of a match against Germany played in the then Federal Republic. Historian Friso Wielinga has described the nation’s mood on that day as ‘the rare ecstasy of a small country that had demonstrated its superiority to its larger and more powerful neighbour.’

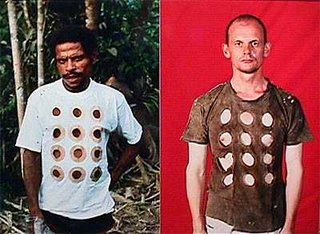

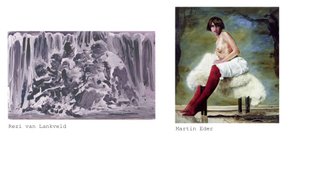

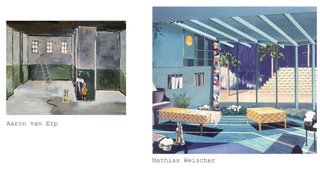

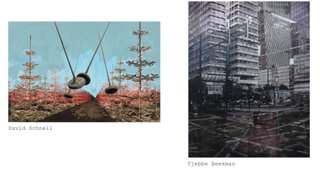

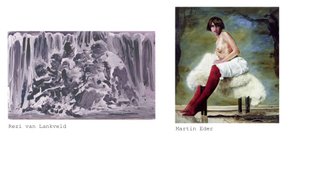

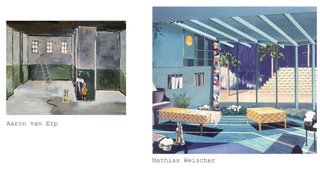

In a light-hearted nod to the constantly changing social relations between the two countries, this group exhibition will confront three young artists from the Netherlands with three of their peers from Germany, arranged in three sets: Aaron van Erp and Matthias Weischer, Tjebbe Beekman and David Schnell, and Rezi van Lankveld and Martin Eder. All six artists give a modern twist to traditional romantic themes, each in his own particular way and without shying away from (often subtle) references to the structures, ambitions and anxieties of society today. Matthias Weischer and Aaron van Erp make ‘psychogrammes’: paintings that are an enigmatic depiction of the emotional messiness of modern life. David Schnell and Tjebbe Beekman apply the strategy of the sublime to the contemporary landscape, manipulating the perspective and other aspects so that the viewer feels caught up in something beyond his control. Martin Eder and Rezi van Lankveld produce work in which eros and thanatos are two sides of the same coin – their pictures transport us to the midst of a postlapsarian paradise and delve deeper into the human subconsciousness.

Netherlands v. Germany is intended, therefore to explore various aspects of the romantic sensibility in contemporary art. The choice of artists and the matches between them will not only reveal recent developments in German and Dutch art, but also invite the public to engage in an intensive consideration and comparison of the works on show.

Wall of small sketches that i´m working on and very carefully like to share with you.

Wall of small sketches that i´m working on and very carefully like to share with you.